Life in Rome

I have not updated this blog in quite some time because I created it for a class assignment in the spring semester of this past school year. I am now currently studying abroad in Rome, and had the best intentions of keeping this blog updated on the things I see around me in my daily life. However, a jam-packed schedule and a rigorous class on Ancient Roman art has prevented me from sticking to my guns.

May I direct you to my personal blog, Betty Photog, where I post informal film photography and personal accounts of my time in Rome.

But please, continue to enjoy this blog as a quick reference to pieces of Baroque art.

Week 13: Diego Velázquez (1599-1660)

Old Woman Frying Eggs

Diego Velazquez 1617-1619.

Oil on canvas.

National Gallery of Scotland.

Diego Velazquez’s first biographer Palomino described a young Velazquez as very interested in painting from life while under the apprenticeship of Francisco Pacheco (Enggass 182).

This bodegóne, or still life with figures, is one of Velazquez’s first paintings, executed when he was a teen. It exemplifies the young artist’s interest in contrasting textures and points of view to make this scene a truly convincing reality. The mixture of still-life and genre scenes was popular in Spain at this time.

Influence from the Caravaggists can be seen in the stark tenebrism. Each item is depicted individually, as seen in Cotan’s still-lifes, yet has a Caravaggist extreme naturalism. The composition is pressed against the foreground with a dark, shallow background.

This piece is remarkable because it appears to be a natural, real scene to the naked eye. However, on closer examination, some items, such as the bowl of eggs and other items on the table, all appear to have their own perspective. No one thing is seen at the same point of view. We are looking down on the pot of eggs, yet the woman is in perfect profile.

Enggass, Robert and Jonathan Brown. Italian and Spanish Art 1600-1750; Sources and Documents. Palomino’s Life of Velazquez. pp. 180-196. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1970.

Christ in the House of Martha and Mary

Velazquez 1618.

Oil on canvas.

National Gallery, London.

This painting is typical of Velazquez’s style to come. It features a scene in the foreground with another scene either in the background, reflected in a mirror (so, behind the viewer), or in the painting on the wall. This type of double-subject matter has been seen in earlier paintings which featured Biblical scenes subordinate to the landscape in which they take place, and in genre scenes such as Pieter Aertsen’s Meat Stall that features the Flight into Egypt framed in the background by the meat cart up front. Velazquez would continue to paint these ambiguous double-subject paintings, including the more famous Las Meninas in 1656.

The scene in the foreground shows Mary and Martha tending to their house. It derives from a story in the Gospel of Luke in which Christ came to visit Mary and Martha. This portion of the story is shown in the upper right corner in what is most convincingly a mirror. The two scenes have an opposite direction of lighting. Again, we see Velazquez’s interest in naturalism in the varying textures of the items on the table. This painting fits into three of the popular subjects in Spanish art during the Baroque: religious, still-life, and genre.

Feast of Bacchus

Velazquez 1628-1629.

Oil on canvas.

Museo del Prado, Madrid.

Although from Seville, Velazquez painted this scene in Madrid. It is a different take on the popular subject of Bacchus. Unlike Caravaggio’s Bacchus, Velazquez’s is surrounded by drinkers. They are all, in fact, peasants dressed in contemporary clothing. Bacchus stands out as a very Classical god and has a much lighter skin color, separating him from the peasants. Tomlinson argues that Bacchus seems almost too human (90). The individualized expressions and poses of each man in this painting is a reflection of Velazquez’s interest in extreme naturalism.

Velazquez presents his Bacchus and the drinkers full length against a a landscape. He uses almost monochrome brown to unify this painting. It shares a similar tone with the Caravaggist Ribera’s Drunken Silenus from around the same time. There is a hint of Velazquez’s signature still-life in the foreground at the drinkers’ feet. This painting is a deviation from the court portraiture Velazquez had been doing up until this point.

Tomlinson, Janis. From El Greco to Goya: Painting in Spain 1561-1828. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1997.

Forge of Vulcan

Velazquez 1630.

Oil on canvas.

Museo del Prado, Madrid.

This painting marks a change in Velazquez’s style. He had taken a trip to Italy in 1629. While there, his primary biographer Palomino tells us that the Sevillian artist was exposed to the great works by Tintoretto, Titian, Veronese, Federico Zuccaro, Raphael, and Michelangelo to name a few (Enggass 186-187). This had a vast impact on his style from there on out.

This painting is composed very Classically in that it features full length figures across the foreground of the picture plane. A move away from Caravaggio’s extreme naturalism can be seen in Velazquez’s nearly idealized figures. The graceful stances of the half-nude men contrast Velazquez’s frumpy peasants in Bacchus. The artist uses gesture, expression, and affeti. This scene takes place neither in a landscape nor an ambiguous dark space, but a rather developed sense of place.

Enggass, Robert and Jonathan Brown. Italian and Spanish Art 1600-1750; Sources and Documents. Palomino’s Life of Velazquez. pp. 180-196. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1970.

Juan de Pareja

Velazquez 1650.

Oil on canvas.

For exhibit in the Pantheon, now in Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Velazquez was a renowned portrait painter, and this painting of his servant and pupil is no exception to the artist’s exquisite craftsmanship. His use of brushstrokes gives this portrait its life-like textures.

Velazquez painted this for a competition to have a piece of art in an exhibition in the Pantheon in 1650. It is the first work he executed while on his second trip to Rome. Juan is featured at three-quarter length, showing only one hand. His gaze is off the picture plane, yet unfocused, as if staring over the viewer’s shoulder. The background is non-existent, yet Juan inhabits the space nonetheless. Velazquez’s use of scumbling – layering light colors over dark – gives the ambiguous background a sense of place. Velazquez also uses daubs of paint in a technique called impasto to create the highlights on Juan’s features. An Italian influence is obvious in this portrait. Velazquez may have beenlooking at Ribera’s Democritus from 1630 (right).

Rokeby Venus

Velazquez 1651.

Oil on canvas.

Now in the National Gallery, London.

This painting is another example of Velazquez’s ability to paint two different points of views and light sources within one composition. One of many, this particular double feature uses a mirror to convey the second point of view. We call this piece a Venus because the putto has arrows tied behind his back – Cupid.

The entire piece shows Velazquez’s Italian inspiration, notable Titian’s. It is painterly in style. The reflection of the young woman’s face is especially painterly, perhaps Velazquez’s way of showing off his abilities to paint different surface textures. It is also apparent that Velazquez used a painting technique called borrón. This is a way of glossing paint over multiple layers to create a multi-tonal affect, derived from Venetian use of color.

Velazquez’s Venus is the first painting of a female nude in Spanish art (Sánchez). Although similar in pose to the many female nude paintings to follow, this one is different because Venus’s back is to the viewers. This makes it not only a modest nude, but also an ambiguous nude. The viewer does not know if he is actually looking at a nude woman, because the only thing to give the gender away is the feminine reflection.

Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez. “Velázquez, Diego.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. 25 Apr. 2011 <http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T088463>.

Las Meninas

Velazquez 1656.

Oil on canvas.

Museo del Prado, Madrid.

This is one of Velazquez’s most famous works. Its unclear and ambiguous subject matter is its greatest asset.

The tanglible subject of this piece is the Princess Margarita María with her maids of honor and servants in an actual room in her Alcázar. Velazquez is presented in a self-portrait, painting a large canvas. This painting is probably about the size of the canvas the artist has included in the composition, and so it can be viewed as him painting this particular painting. However, Velazquez’s famous use of pictures-within-pictures confuses the meaning of this painting. On a wall in the background, there is either a portrait of King Philip IV and Queen Mary Anne or a mirror. If indeed a mirror, this means the viewer is in place of the king and queen, or between the composition and the portrait sitters. It is also unclear what the man in the doorway represents.

Many aspects of this painting are executed in such a painterly manner that they appear abstract when viewed closely. This contrasts with the attention to detail Velazquez paid to the subject matter. Every figure is busy in an individual endeavor. Some tend to the Infanta, others are distracted, and Velazquez seems unaware of the ruckus, focused on his painting. The princess’s hair is rendered in such painstaking detail, one could almost see through her fine blonde locks to her elegant costume. The numerous pieces within this composition make it a complex piece, one of Velazquez’s most notable.

Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez. “Velázquez, Diego.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. 25 Apr. 2011 <http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T088463>.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1618-1682)

Imaculate Conception of the Escorial

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo 1660-1665.

Oil on canvas.

Museo del Prado, Madrid.

This painting was a result of a debate on the Immaculate Conception. The Franciscans believed Mary was born free of Original Sin, and so immaculately conceived. However, the Dominicans believed that Mary was conceived like everyone else – with sin, but became purified. Because Murillo had a close connection to the Franciscans, he painted a triumphant Mary on a crescent moon. His Mary is depicted according to the vision of Beatriz de Silva (Marqués).

Murillo executed this painting in an extremely painterly manner, known as estilo vaporoso. Mary stands on clouds and a crescent moon, floating. Four putti tumble about at her feet. This shows Murillo’s exposure to Velazquez and his Italian-influenced works.

Manuela B. Mena Marqués. “Murillo, Bartolomé Esteban.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. 25 Apr. 2011 <http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T060472>.

Juan Sánchez Cotán (1560-1627)

Still Life with Quince, Cabbace, Melon, and Cucumber

Sanchez Cortan 1602-1603.

Oil on canvas.

Fine Arts Gallery, San Diego, California.

This still life is considered to be the Spanish artist Juan Sanchez Cotan’s masterpiece. He painted many still-life scenes similar to this one, in fact. Each included various fruits and vegetables, separated from one another, againsts a black background. This was to evoke a meditation on each item in the composition, similar to the contemplation recommended by St. Ignatius Loyola in his Spritial Exercises (Tomlinson 58). Indeed, Cotan was a pious man and has been reputed to have given up his possessions to live in a Carthusian monastery after painting this (San Diego Museum of Art).

Still-life paintings were popular in Spain during the Baroque (as did they gain popularity in Italy, as well). This particular piece was exuctued during the time of Caravaggio’s early works including his extremely naturalistic still-life paintings. Life the great Italian master, Cotan’s compostion features a cucumber that teeters on the edge of its platform. It extends into the viewers space and creates tension. Each item in this still-life is distinctly rendered, catching the attention of the viewer equally. The vegetables are arranged in a mathematical curve within the frame.

Tomlinson, Janis. From El Greco to Goya: Painting in Spain 1561-1828. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1997.

San Diego Museum of Art. “25 Works of Art You Must See.” <http://www.sdmart.org/art/quince-cabbage-melon-and-cucumber>

Week 11: Bernini (1598-1680)

Aeneas, Anchises, & Ascanius

Bernini 1618-1619.

Marble.

For Cardinal Scipione Borghese, now in Galleria Borghese, Rome.

Working with his father Pietro, a sculptor, Bernini was exposed to opportunities for patronage. Chief among them, and his first major patron, was Cardinal Scipione Borghese. Young Bernini’s first monumental commission was for Aeneas, Anchisis, and Ascanius. This sculpture (and patronage) foreshadows the development of Bernini over the next few years.

This multi-figural sculpture depicts a scene from Roman history. Aeneas carries his father Anchises out of Troy, while Ascanius follows closely behind. The composition of the three figures is very tight and vertical. Bernini’s Mannerist inspiration can be seen in the serpentinata upward twist of Aeneas as he holds his father to his left side. This compositional idea is expanded in Pluto and Persephone.

Bernini seems to have been looking at Michelangelo and Raphael in conceiving the idea for this composition. The musculature of the men comes from Michelangelo’s countless sculptures and paintings. The figure of the man carrying another man in Raphael’s Fire in the Borgo seems to have lent some inspiration to this sculpture as well.

The problem with this sculpture is that not all characters can be seen at once. True, one can move around it to see all three, but Bernini had solved this problem in later sculptures.

Pluto & Persephone

Bernini 1621-1622.

Marble.

Commissioned by Cardinal Scipione Borghese, as a gift for Cardinal Ludovisi, now in Galleria Borghese, Rome.

This multi-figure sculpture appears to be a maturation and refinement of Bernini’s earlier Aeneas, Anchises, & Ascanius. Pluto strides forward as Aeneas had, both men carrying a person in a serpentinata spiral. Although Aeneas had been carrying his father in order to save him, Pluto is carrying Persephone away to take her. This sculpture is successful in showing all the action in a single view, yet the narrative can be satisfied from any viewpoint.

As opposed to the static verticality of the Aeneas group, Pluto and Persephone can be considered High Baroque in the tension created by their dynamic movements. The struggle and resistance of Persephone intensifies the drama of the scene. Inspired by Hellenistic sculpture, Persephone’s intense facial expression conveys her frantic emotion (Wittkower 6). Bernini used hair and drapery to enhance the affeti of his pieces.

Another one of Bernini’s major successes within this piece is his rendering of flesh with verisimilitude. Bernini was able to create the tender flesh of Persephone out of stone. Imprints of Pluto’s strong hands are indicated on her thigh. Contrasting her supple body is the musculature of the Michelangel-eqsue Pluto.

David

Bernini 1623.

Marble.

For Cardinal Scipione Borghese, now in Galleria Borghese, Rome.

Over 100 years after Michelangelo’s David, Bernini executed the same subject in the same material in High Baroque style.

Inspired by the single view point of the Renaissance and the freedom of Mannerism, Bernini combined the two past styles, creating an entirely new Baroque dynamism, seen in this sculpture (Wittkower 11). It was originally intended to be placed in a niche, against architectural elements. However, David has more than one viewpoint. The sculpture also takes up more than one pictorial plane.

As was typical of Bernin’s concetto, we catch Bernini’s David mid-action, just about to strike a stone at Goliath (Wittkower 19). His determination shows in his face: tight lips, protruding chin, and furrowed brow. The dynamic stance of David can be seen in Annibale Carracci’s Polyphemus Furioso and Myron’s Classical Discobolus.

Unlike Michelangelo’s David, Bernini’s is almost life-size. This creates a relationship with the viewer that any colossal statue can never attain. The subject life-sized sculpture exists in the viewer’s world. Bernini’s David is almost on the same level as the viewer, Goliath could be standing right behind the viewer.

Bernini’s sculpture of David is an example of the mastery of nature, which Baroque artists strived for. Hundreds of studies of human faces, expressions, reactions, and emotions were being documented at this time. Bernini fully encompassed what it must actually feel like to be a young hero up against a giant monster. It is believed that Bernini looked at himself in the mirror, modeling David on himself, just as Caravaggio had in his double self-portrait.

Martin, John R. Baroque. New York: Harper & Row. 1977.

Wittkower, Rudolf. Art and Architecture in Italy 1600-1750. Vol II. High Baroque Yale University Press. 1958.

Bernini 1623-1634.

Gilt bronze.

St. Peter’s, Vatican.

Between Michelangelo’s dome and Carlo Maderno’s confessio is Bernini’s monumental baldacchino. It hovers above the high altar of the church and the grave of St. Peter (Mezzatesta). The structure consists of four gilt bronze spiral columns. These mimic the original twisted columns from Old St. Peters. The original marble columns can be found in the pier-niches of this same church. The originals are believed to have been from the Temple of Solomon. The erection of such a baldacchino with reference to these special columns links Pope Urban VIII with Solomon and his Divine Wisdom.

The form of the baldacchino comes from Counter Reformation church architecture. The Council of Trent decreed that the altar should be able to be seen from the back of the church. Church used to have rood screens, keeping the public far away from the Eucharist. The open structure of the baldacchino invites the worshipper in. The heavy metal canopy is further made to appear lighter by its open space between ribs. Designed to look like a canopy, the flaps look as though they could sway in the breeze. Four angels and a globe at the top anchor the baldachhino down.

Bernini shows an interest in nature on the columns. Not only are the Barberini bees depicted in gold, but olive branches also climb up the spiraling columns. This as well as its open spaces make the heavy metal structure appear to be springing up from the crypt with life.

Michael P. Mezzatesta and Rudolf Preimesberger. “Bernini.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. 7 Apr. 2011 <http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T008287pg2>.

Tomb of Urban VIII

Bernini 1627-1647.

Bronze, gilt bronze and marble.

St. Peter’s, Vatican.

The tomb of Urban VIII is the first tomb Bernini was commissioned to execute. It is located in the apse of St. Peter’s next to the relocated tomb of Paul III. The pairing of these two tombs provides a contrappasto of styles and shows evidence that Bernini may have been looking at Michelangelo’s Medici tombs for inspiration.

An over life sized bronze statue of Urban VIII is in the center of the piece, his arm outstretched in a blessing. At his feet is the allegory of death writing Urban’s name in the book of the dead. Flanking these figures are two allegories: Charity and Justice. The general set up of these figures became a model for prestigious tombs to come.

All figures in this composition seem to have been caught mid action. Charity is nursing a child, Justice looks to have given up, and the winged skeleton’s bronze parchment slumps as he attempts to inscribe Urban’s name.

Michael P. Mezzatesta and Rudolf Preimesberger. “Bernini.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. 7 Apr. 2011 <http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T008287pg2>.

Bust of Scipione Borghese

Bernini 1632.

Marble.

For Scipione Borghese, now in Galleria Borghese, Rome.

Compared to Bernini’s earlier bust of Paul V, this bust of Scipione Borghese is full of life and vigor. The individualized features are further made custom by the cardinal’s subtle movements. Scipione appears to be mid-sentence, speaking with vitality, fully engaged with someone or something.

Cardinal Scipione Borghese was one of Bernini’s major patrons. At the time of the carving of this bust, Bernini had moved on from his patronage. This shows a strong relationship between the two and Bernini’s admirable reputation among the papal elites.

The story of the crack in the marble of this bust almost equates Bernini with Michelangelo. In the latter’s case, the great master took on the job of carving a flawed piece of marble that no one wanted to attempt. In the end, the beautiful colossal David came of if. Likewise, an unforeseen flaw in the marble Bernini was carving revealed itself around the forehead of the cardinal. It appears that Bernini attempted to assimilate it into the wrinkles of the forehead made by the cardinal’s expression. However, Scipione ordered a new one to be made, and Bernini carved it almost overnight. Although two different outcomes to the story, both involve master sculptors emerging more than triumphant from the ordinary obstacles many sculptors face.

Bernini 1631-1638.

Marble.

St. Peter’s, Vatican.

This sculpture in St. Peter’s basilica stands above the Holy Lance, one of four relics housed by the church. It is placed in a niche in one of the piers that holds up the dome over the crossing of the nave.

Although St. Longinus is executed in monochrome marble, Bernini’s sculpting techniques add a dazzling quality almost like color. The saint’s chest is left unpolished, chisel marks in tact. This created a matte effect, causing the light not to reflect as intensely, just as it would off human skin.

As in Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne, drapery is used to assist in conveying the spiritual mentality of the figure (Wittkower 7). It flows in such a direction that leads the eye to the relic below. It seems to billow in a wind unfelt by the viewer, but realized upon seeing its imaginary effects.

This statue if out of the viewer’s reach, but Bernini employed another device to place the sculpture in the same realm as the viewer. St. Longiuns looks up toward the light coming from the dome. The viewer can do the same and experience its effects.

Wittkower, Rudolf. Art and Architecture in Italy 1600-1750. Vol II. High Baroque Yale University Press. 1958.

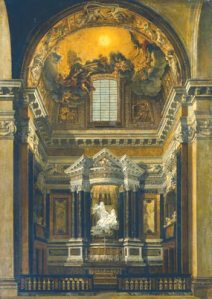

Cornaro Chapel

Bernini 1647-1652.

Marble and bronze architecture, marble sculpture and relief, stucco and fresco vault.

S.M. della Vittoria, Rome.

The decoration of this family chapel at the request of Cardinal Federigo Cornaro is considered Bernini’s most complete work. Indeed, the painting, sculpture, and architecture come together as a cohesive whole, revealing the mystical world envisioned by the chapel’s centerpiece, Ecstasy of St. Teresa.

As seen in Bernini’s work on the Baldacchino of St. Peter’s, the artist successfully combines art and nature. Bernini took the liberty to altar the architecture of the church to control his light source on the sculpture and the paintings. St. Teresa sits in a niche with a hidden window above it. The natural light pours in and glitters off the gold beams. His combination of the two worlds of art and nature can be seen in the chapel’s program at large: the material world versus the heavenly world. The natural world is depicted on level with the viewer in sturdy materials whereas the heavenly world – the realm never seen by human eyes except through art – is shown above the viewer, out of his or her reach. The bright light from the window also obscures the viewer’s perception of the scene on the ceiling.

Although the chapel as a whole was created to simulate the experience of St. Teresa, the ordinary viewer can never see it the way Bernini and the Cornaro family had. Railings at the edge of the chapel keep the viewer at a distance, controlling the viewpoint of each piece of art within. The patrons of this chapel are always inside it, sculpted in a marble relief on a sidewall. This imitates a choir box or balcony. Although carved out of very hard marble, Bernini managed to create the illusion of depth in low relief in the background. One of the four figures is aware of and paying attention to the scene of ecstasy while the other talk among themselves.

Michael P. Mezzatesta and Rudolf Preimesberger. “Bernini.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. 7 Apr. 2011 <http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T008287pg2>.

Alessandro Algardi (1598-1654)

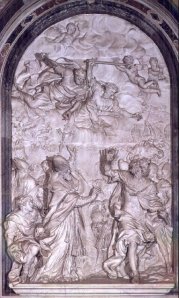

Meeting of Leo I and Attila

Alessandro Algardi 1646-1653.

Marble.

St. Peter’s, Vatican.

A contemporary foil to Bernini, Alessandro Algardi received a commission from Pope Innocent X for a history relief scene of Pope Leo the Great, a vision of Sts. Peter and Paul, and Attila (Preimesberger). Algardi is unlike Bernini in that his style is much more Classical than High Baroque. He was trained in the Bolognese Academy and was closed friends with Domenichino. Such a scene from the 5th century was of interest to the current pope because it showed Pope Leo saving Christianity from the barbarians.

The figures in this monumental relief are Classically positioned in two separate realms: earth and heavenly vision. This is reminiscent of Renaissance compositions including visions. However, this relief contains a very Baroque aspect. Figures at the bottom are carved in such high relief that their limbs are sculpted in the round, literally protruding out of the actual picture plane and spilling over the architectural frame. Algardi used a terracotta modella in preparation for this relief. With the terracotta, he was able to sculpt it using an additive method rather than subtractive.

Rudolf Preimesberger. “Algardi, Alessandro.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. 7 Apr. 2011 <http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T001772>.

Week 10: Pietro da Cortona (1596-1669)

http://todaysnewsart.files.wordpress.com/2009/07/cortona_rape_of_the_sabine_women_01.jpg?w=500&h=332

Rape of the Sabine Women

Pietro da Cortona 1629-1631.

Oil on canvas.

For Palazzo Sacchetti, now in Pinacoteca Capitolina, Rome

Pietro da Cortona’s painting for Giovanni Francesco Sacchetti and emulates many characteristics of Baroque painting (Merz). It also closely follows Heinrich Wölfflin’s Principles that define Baroque art (Minor 28).

Pietro rendered this scene in a painterly manner, inspired by Titian. The figures are not plastic or defined by sharp contour, and edges are blurry. There are quite a few picture planes in this single composition, each one set at a distance that is farther from the viewer (indicated by smaller figures than the plane in front of it.) This idea of planer recession is adapted from Renaissance techniques, but made Baroque in that the space seems infinite.

This scene of chaos is presented to us in such a way that leads us to believe we are only seeing a portion of the action. There are no repoussoir figures to keep the viewer out of the painting – for all we know, we can be in the midst of the scene as it goes on, encircling us. It does, however, have a theater, stage-like quality about it. Figures on the sides seem to be entering and exiting from the wings. There is a lack of co-extensive space.

Pietro follows a sort of decorum in the depiction of this scene. Perhaps inspired by Bernini’s Pluto and Persephone, or the other way around, the figures in Pietro’s Sabine composition seem to dance across the picture plane in intense contrappasto. The strong dark-skinned men grab into the pale, flailing women, a contrast in color and direction. The figures vibrate in anguish.

There are a number of characters in this composition. Pietro da Cortona unites them in color and subordination. One does not look at this scene and see individual players, but a scene as a whole with all parts working together, relying upon each other for context. He sprinkles the composition with pops of color and chiaroscuro. This, along with the strong diagonal forces, controls the eye throughout the painting.

Merz, Jörg Martin. “Cortona, Pietro da.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. 31 Jan. 2011

Minor, Vernon Hyde. Baroque & Rococo: Art & Culture. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, Inc.

http://www.shafe.co.uk/crystal/images/lshafe/da_Cortona_The_Triumph_of_Divine_Providence_1633-39.jpg

Glorification of the Reign of Urban VIII

Pietro da Cortona 1633-1639.

Fresco.

Gran Salone, Palazzo Barberini, Rome.

Pietro da Cortona’s painting of the ceiling of a Salon in the Palazzo Barberini set a new standard in scale for ceiling paintings. It is the largest private ceiling painting in Rome. The entire composition was executed as one continuous painting utilizing di sotto in su and pushing quadratura to its limits. The subject is the apotheosis of Pope Urban VIII, a new and influential idea at the time. It is based on a poem by Francesco Bracciolini (Enggass 103) containing many episodes which are subordinate to the whole epic composition.

Many photographs attempt to show this painting in its entirety. However, Pietro did not intend for the view to see it all at once. He had the direction of the viewer’s own movements in mind. Upon entering this room, one sees the far end of the painting first (Minerva and the giants). The central scene at the top is oriented vertically for the viewer to comprehend while still di sotto in su. When viewed from directly below as this photo shows it (and as a person may never be able to actually see it), the lateral figures appear to be stretched out. Once the viewer is oriented in a natural location beneath the painting, the composition makes sense. Pietro’s use of Venetian atmospheric effects and perspective helps resolve issues with di sotto in su.

Besides an apotheosis, this is an allegory of Divine Providence. It is believed and accepted that the pope was elected through Divine Providence. Many other allegorical figures are scattered about the entire composition. The main event shows Rome crowning Religion with the papal tiara. A putto helps Religion hold the papal keys. Faith, Hope, and Charity surround the Barberini bees.

As aforementioned, Pietro used quadratura in this piece in an extreme fashion. The architecture of the room seems to extend far above the actually ceiling. The fictive architecture is painted to resemble marble. Atlas figures hold up the cornices. Figures within the lateral scenes step out of their frames and into the architecture, blurring the line between flesh and stone. This painting comes to life as the marble figures mimic poses of the narrative figures (left; Hercules, the Forge of Vulcan, and Prudence).

Enggass, Robert, Jonathan Brown. Italian and Spanish Art. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. 1970.

Trinity in Glory & Assumption

Pietro da Cortona 1647-1651 and 1655-1660.

Frescoes.

Santa Maria in Vallicella, Rome.

Decorating the dome of the Chiesa Nuova in Rome was Pietro da Cortona’s first major commission in the Eternal City. He began executing a Trinty in the dome in 1647 (Merz). In this composition, he arranged the group of figures separately from each other, as opposed to his jumbled compositions like in the Barberini Palace. Trinity is painted di sotto in su.

Four years after completing the dome at S.M. in Vallicella, Pietro was commissioned to paint the apse of the half-dome above the altar. The subject for this fresco was The Assumption. Pietro executed this scene in a similar fashion as the Trinity, however, both compositions were in separate spheres. Pietro’s task was to find a way to unify both of these scene that are very clearly separated by architecture. Pietro’s solution includes an almost leaping Mary. She sees to be about to fly out of her apse and into the dome to join her Son in the Trinity.

Just like in the Barberini Salon, the viewer’s own movement through the room controls his or her experience of the paintings. In the church, it is difficult to see both compositions in the dome and the apse at the same time. Upon entering the church, one sees the Assumption at the altar. The viewer’s experience changes upon approaching the dome. Once near the dome, some of the Trintiy can be seen along with the Assumption. Once under the dome, the viewer is able to see the entire Trinity and experiences the Virgin Mary’s final destination. This sense of a changing composition upon movement of the viewer is one of Pietro da Cortona’s greatest devices in his paintings.

Jörg Martin Merz. “Cortona, Pietro da.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. 1 Apr. 2011 <http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T019663>.

Transport of the Holy House

Pietro da Cortona 1664-1665.

Fresco.

Santa Maria in Vallicella, Rome.

The fresco on the main vault of the church depicts St. Philip Neri’s vision of the Virgin and Child during the transporting of the Holy House of Loreto. It is painted primarily di sotto in su. Although the composition would look strange on a vertical wall, Pietro also executed this as a quadro riportato.

The unusual orientation of this painting – or lack thereof an actual orientation – was made possible by the dearth of subject matter in the very center. This is where the eye would naturally fall in order to make sense of the composition’s orientation. Lack of figures of subject matter in this area causes the eye to wander around the rest of the painting without regard to its realistic sense of place.

There is a hint of quadratura in this fresco. The architecture painted in the scene is very steep, emphasizing the di sotto in su, as figures must lean over elements to be visible.

Although there is quite a number of figures in this composition, there are only a select few necessary to the story. These are easily identifiable, making this an appropriate piece in the Counter-Reformation. Its compliance with the Decrees of Trent also account for its lack of true di sotto in su, for seeing the undersides of figures in such attire as depicted here would be inappropriate in a sacred setting.

Kemp, Martin. The Oxford History of Western Art. New York: Oxford. 2000. p.200.

Process of S. Charles Borromeo during the Plague in Milan

Process of S. Charles Borromeo during the Plague in Milan

Pietro da Cortona 1667.

Oil on canvas.

S. Carlo ai Catinari, Rome.

Painted very late in Pietro da Cortona’s career, this canvas painting shows how the artist’s style changes in response to subject matter. The Caravaggesque chiaroscuro and tenebrism are certainly appropriate in this scene of disaster and chaos.

In the scene, St. Charles Borromeo uses the true nail of the Cross to ward off the plague in Milan. This miracle was important subject matter for the legitimization of saints during the Counter-Reformation. It seems as if the style in which Pietro painted this scene has been adjusted to fit the dismal subject matter, following a decorum on such works.

Although much more Classical in composition compared to Pietro’s earlier work, this painting still contains many Baroque elements. The dark scene is punctuated by bursts of light from candles. This was a characteristic of Baroque artists trying to flaunt their ability to represent multiple light sources. The chaotic scene is full of diagonals and movement. However, the action is taking place right up front in the foreground. Two figures at the bottom corners frame the scene, keeping it within the picture plane. There is a slight hint of distance in the background.

Andrea Sacchi (1599-1661)

St. Gregory and the Miracle of the Corporal

St. Gregory and the Miracle of the Corporal

Andrea Sacchi 1625-1627.

Oil on canvas.

Commissioned for St. Peter’s, now in Pinacoteca, Vatican.

This painting is an example of Sacchi’s matured style. It contains both Classical and Baroque elements. This is a story of a miracle; the piercing of a sacred cloth with a dagger. This cloth was used to clean the chalice in the Mass. It bleeds from its puncture.

The figures are arranged in a Classical triangle. However, the two figures at the bottom of the group have their backs to the picture and look up at the pope. This dynamic spiraling turns the triangle into a pyramid. The composition as a whole has a contrappasto between those in disbelief, now realizing their Faith, and those who believed all along.

Sacchi painted this in warm Venetian colors and tones. There is a painterly quality to his brushstrokes. He had also looked as masters such as Raphael in his studies. This is evident in the psychology of the painting as well as the composition.

Wittkower, Rudolf. Art and Architecture in Italy 1600-1750. Vol II. High Baroque Yale University Press. 1958.

Divine Wisdom

Andrea Sacchi 1629-1633.

Fresco.

Antechamber to private chapel in Palazzo Barberini, Rome.

Andrea Sacchi’s ceiling fresco in the Palazzo Barberini was painted before Pietro da Cortona painted the ceiling of the Gran Salone. The two compositions are very different from each other. Andrea Sacchi’s is considered more Classical, yet utilizes di sotto in su, as was vogue, inspired by Lanfranco’s Council of Olympian Gods (Harris). However, one cannot help but notice the lack of depth of the background.

Because this was a private room, the decorum of the Counter Reformation did not apply here. This scene is from the apocryphal Wisdom of Solomon. It referenced the beauty of Wisdom. Each character in this composition is an allegorical figure. Sacchi’s accomplishment in portraying these figures is in their affeti. The figures do not need much context to convey who they are, they simply just are. Their gestures express all one needs to know.

Since this room led to the private chapel of the Barberini, it acted like a nave of a church. The doors of the chapel were right below the bottom of the composition on the ceiling.

Ann Sutherland Harris. “Sacchi, Andrea.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. 1 Apr. 2011 <http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T074853>.

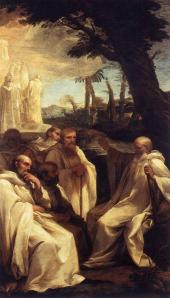

Vision of St. Romuald

Andrea Sacchi 1631.

Oil on canvas.

For S. Romualdo, Rome, now in Pinacoteca, Vatican.

Andrea Sacchi’s work in the Barberini Palace put him in favor with the family. Cardinal Lelio Biscia commissioned an altarpiece by Sacchi for the new church of the Camaldolese Order.

The altarpiece contains a simple, Classical composition. Sacchi depicts the monks in their characteristic white robes. St. Romuald tells the others about his vision and points behind the listening figures. Behind them is his vision. Even further behind the vision is distant landscape. A warm golden light comes from the vision and shines on the figures of the foreground mostly illuminating St. Romuald and another listening monk.

The figures each have very individualized features. This makes for a personal experience for the viewer. This is a contemplative piece that evokes the viewer to concentrate just as the figures in the painting are.

Week 9: Domenichino (1581-1641)

Alms of St. Cecilia

Domenichino 1613-1614.

Fresco.

Polet Chapel, S. Luigi dei Francesi, Rome.

Compared to the Caravaggio St. Matthew pieces in the same church, Domenichino’s St. Cecilia fresco is radically different. Executed only over 10 years after Caravaggio’s dark, tenenbristic laterals and altarpiece in the Contarelli Chapel, Domenichino’s composition of alms giving has a much lighter palette. This is due to its medium, fresco. Many other aspects of this piece make it much different from Caravaggio’s Baroque style.

Domenichino appears to be reviving Bolognese Classicism with his St. Cecilia fresco. The composition of figures as a whole creates a triangle that is very much in the foreground. This establishes stability. Within the triangle, however, there is still much movement and strong diagonals. The two figures at the bottom corners of the composition mirror each other, creating a continuity of movement within the scene.

Indirect quotes from Raphael can be seen in this piece as well as others of the time period and style. Instead of directly quoting figures used in earlier pieces, as done in the Late Renaissance and Maniera, Baroque artists captured the essence of a figure’s pose, then had a live model reenact the pose, and fianlly drew the model from different angles. Thus, they made their own adaptation of recognizable figures from the past masters while making them their own.

This scene of alms giving was important during the Counter-Reformation because it emphasizes the importance of a saint and her good works.

Last Communion of St. Jerome

Domenichino 1614.

Oil on canvas.

For Congregation of St. Jerome of Charity, now in Pinoteca Vaticana, Rome.

Domenichino’s St. Jerome shows his familiarity with the Carracci version, but also created controversy in that it looked too similar.

In Domenichino’s piece, the composition is flipped from Agostino Carracci’s original. Jerome is now on the left side, looking right to the priest handing him the Eucharist. Everyone in the composition is focused on the main event – Jerome in penitence receiving his last Communion (Cropper). These are two sacraments that the Protestants would not accept. This painting is a stronger defense of those sacraments during the Counter-Reformation than Carracci’s. Domenichino even features items that would be found at the altar during such a ceremony such as candles and a chalice.

Domenichino’s St. Jerome is arguably more Baroque than Carracci’s in that it encompasses far distant space. Both compositions feature a piece of architecture in the background that is open to reveal a landscape beyond. Carracci’s scene seems to eliminate most planes of the middle ground and jumps straight to the distant background. Domenichino, on the other hand, takes the time to show a receding background with many planes in between.

Elizabeth Cropper. “Domenichino.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. 22 Mar. 2011 <http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T023167>.

Vocation of Ss. Peter & Andrew

Domenichino 1625-1628.

Fresco.

S. Andrea della Valle, Rome.

The center-piece of the dome-like apse spandrel frescoes at S. Andrea della Valle is a Vocation by Domenichino. It shows Christ, fishermen, and Saints Andrew and Peter.

Domenichino faced a technical problem with the shape of the surface for the fresco. It is rounded, concave. He devised a way to make each painting appear quadro riportati, yet also appear to only be a window into the world of the apostles. This scene, like the others in this apse, gives the illusion that it extends beyond the picture frame. There are hints of a background landscape in this boat scene, as well.

The action of this vocational scene is happening in the foreground. The figures form diagonals in their interactions with one another. The most prominent can be seen in the long stick one of the men on the boat has. It even seems to mimic the ribbing of the dome.

Christ’s gesture recalls that of Caravaggio’s Calling of St. Matthew Christ. He stands off to the side, seemingly not quite fitting in with the rest of the characters in the scene. His arm is extended and he points to the chosen ones with a languid finger. Caravaggio derived this from Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam from the Sistine Chapel ceiling (1508-1512).

Elizabeth Cropper. “Domenichino.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. 22 Mar. 2011 <http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T023167>.

Guercino (1591-1666)

Aurora

Guercino 1621.

Fresco.

Casino Ludovisi, Rome.

Guercino’s ceiling in the Casino Ludovisi marks a transition from quadro-riportato scenes to the use of illusionistic di sotto in su and quadratura.

Unlike quadro-riprotato, both di sotto in su and quadratura give the illusion that the ceiling is opening up, or that there is a continuation of the internal architecture. In his Aurora, Guercino used extreme foreshortening in the center of the composition. This is an example of di sotto in su, which means “seen from below.” If the event of Dawn being brought in by chariot were happening above us, this is what we would see: the under side of the horses, the lower and foreshortened side of the chariot. Dawn would have to lean over the chariot, as she does here, in order to be visible. The illusion of the continuation of the interior architecture extending into the illusionistic open sky is an example of quadratura.

Although Aurora is more di sotto in su than quadro-riportato, one still must orient himself in a fixed position to read the center of this painting. The surrounding scenes also must be read from their own fixed point of view, below. In this sense, Guercino has yet to fully master this illusionism. This is not a fully unified illusionistic ceiling.

Burial of St. Petronilla

Guercino 1622.

Oil on canvas.

Altarpiece of St. Peter’s, now in Musei Capitolini, Rome.

This colossal altarpiece carries an unclear message that is up for discussion.

Guercino was commissioned to paint this altarpiece in 1622. One would assume that such a major commission would render a clear, unambiguous composition and message. St. Petronilla is depicted twice, once in the heavenly realm above and again in the earthly realm below. This is called The Burial, but it is unclear if she is being buried or being removed from her grave. It was common for the bodies of deceased saints and notable people to be moved from their original gravesite to a new one for commemorative purposes. Because there are two halves to this altarpiece, one must decided if the upper portion is a vision, perhaps divine inspiration to the digger attempting to find and move her body. Or, one must consider if that is the saint’s resurrection to Heaven.

The two worlds are composed very Classically. Everything is happening in the foreground. There is little indication of background or recession, except for a piece of architecture directly behind the action on earth. No one below seems to be aware of what is happening in the scene above, however, Petronilla’s face is pointed directly at it, implying that she is the only one aware of it, so perhaps this is her burial scene. Likewise, a man appears t be under Petronilla in the grave, it is more likely that he is pushing her up rather than helping to lower her in.